Listing AI use cases is an avoidance mechanism

Most organisations get off course as soon as they create a list of AI use cases.

Most organisations get off course as soon as they create a list of AI use cases.

The list is probably fine. And lists travel well. They create something a board can read, something an executive can sponsor, and something a team can populate quickly. In a pressured environment, “show me the use cases” feels like the most responsible question in the room.

But it’s a trap.

Pressure creates the wrong starting line

Boards and executives are being asked to spend money, take risk, and defend decisions in public. AI is the backdrop, but the pressure is older than AI. It is the pressure to surface something visible. Something that signals motion.

In that environment, “show me the use cases” becomes the safest demand in the room. It sounds concrete. It looks managerial. It creates artefacts that can be counted and presented.

A list also gives people a way to avoid the most uncomfortable part of the conversation. It creates the appearance of forward movement without forcing agreement on what matters, what must be protected, and what is allowed to break.

I’m not saying that use cases are useless. I’m saying that use cases are the wrong place to start.

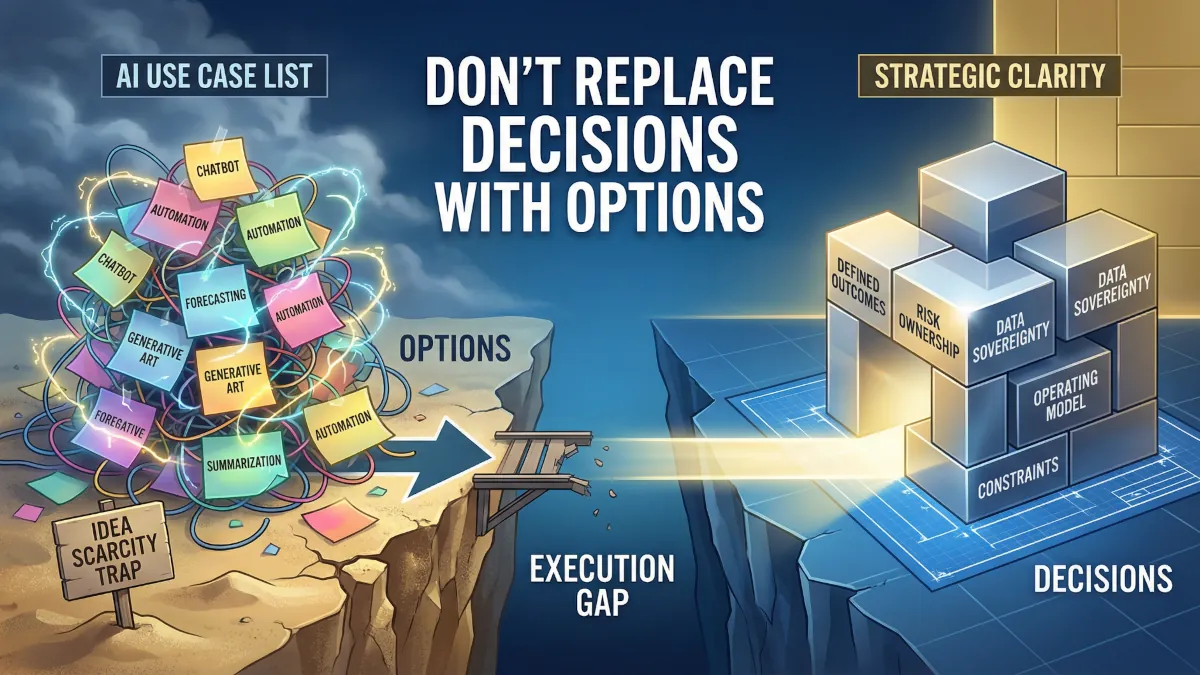

Idea scarcity is not the constraint

The fear that organisations lack ideas for AI is misplaced. Ideas are abundant, especially when executive attention and budget are present.

The real scarcity is decision quality under competing priorities. Clarity about outcomes, constraints, ownership, and trade-offs. A use case request becomes a proxy for leadership work that has not yet been done. It shifts enterprise intent to individual suggestion.

This leads to organisations generating many use cases but struggling to deliver scalable outcomes.

Use cases follow clarity and do not create it

Use cases are outputs of clarity, not inputs.

Clarity means the organisation knows what it is trying to achieve in business terms, what it is willing to give up to achieve it, and what risks it will not take.

When clarity is present, use cases emerge naturally. They are not brainstormed. They are derived.

The question is not “What could we do with AI?” The question becomes “Given what we have decided matters, where does the current system fail to deliver that outcome?”

Starting with use cases skips hard decisions, invites proposals in a vacuum, and rewards novelty. Without clarity, a use case list is not a plan. It is a catalogue of unresolved arguments.

Use case lists grow faster than value

There’s a predictable pattern where the list expands easily. Addition is politically safe. Subtraction creates losers.

Value requires coherence and scales slower than ideas. It needs a small number of outcomes to justify effort and change.

Long lists change behaviour: teams produce options, not results; leaders sponsor themes, not decisions. The organisation becomes busy but ineffective.

The most damaging outcome is diluted focus. If everything is a potential use case, nothing is a priority.

Idea-first thinking fragments the organisation

Use case thinking, while inclusive, fragments the organisation by creating different interpretations. Sales thinks growth. Finance thinks control. Risk thinks containment. Operations thinks efficiency. IT thinks architecture. HR thinks capability.

This fragmentation leads to structural problems: different data definitions, success measures, approvals, procurement, security, vendors, and operating rhythms.

Organisations end up with multiple, small AI initiatives, leading to integration pain. Early use case catalogues become the seed of future complexity. They act as an allocation mechanism for ambiguity.

Quick wins stall when they meet ownership and risk

A “quick win” – a two-week sprint for a prototype – can look impressive initially. Demos, emails, dashboards.

However, when the tool touches live data, fundamental questions arise: data ownership, accountability for errors, data egress, logging, model behaviour, handling of wrong or biased output.

The quick win team is not equipped for these governance and operating model questions. They belong to leaders.

The work stalls. The prototype remains in a sandbox, or the business gets trapped in negotiations with security, legal, data, and compliance.

Risk becomes the villain. Trust erodes.

Quick wins fail not because AI is hard, but because the organisation tries to scale solutions before owning the problem.

Leaders miss the decision that the use case list avoids

The blind spot is believing the list is the decision. It creates an illusion of control but delays actual delivery decisions.

Crucial decisions are about optimisation goals, non-negotiable constraints, and acceptable trade-offs. Customer experience, risk appetite, workforce design, vendor dependency, data sovereignty, auditability, resilience.

Avoiding these decisions leads to later costs disguised as “delivery friction.”

Another blind spot is mistaking visible activity – pilots – for organisational learning. Deployment forces a confrontation with reality.

Months later, the second-order cost becomes structural

Six months after pushing use cases, organisations are fatigued. They have scattered tools and lack sustained performance change.

People become cynical. Boards more demanding. Executives more defensive. Organisations less willing to take risks.

Structural costs accumulate: patchwork controls, ad hoc integrations, exceptions in architecture, multiple small contracts, conflict mediation among functions.

The organisation’s decision-making ability worsens. AI decisions become harder. Platform choices are forced. Governance changes are corrective rather than deliberate design.

The use case list, built to show progress, can end up reducing the organisation’s capacity to progress.

Clarity changes decisions and shrinks the list to what matters

When clarity returns, the dynamic shifts.

AI is treated as an environment exposing weak decisions. The focus shifts from “What can we build?” to “What outcomes must improve, and what must remain true while we improve them?”

The use case list becomes smaller and sharper. It ceases to be a catalogue and becomes a set of implications. Items disappear or collapse into coherent initiatives.

Investment funding is justified by outcomes, constraints, and execution ability – not just use case numbers or demo quality.

Teams are still creative, but creativity is bounded by enterprise intent. Innovation is useful, not noisy. Risk is treated as design input. Quick wins either connect to a scalable path or are not pursued.

Use cases still exist. They just arrive at the right time, as the product of decisions that leaders have already made.

Solving the Right Problem First

By the way, if your AI agenda feels busy but not decisive, you are likely solving the wrong problem first.

This is how we have helped our customers:

- Clarity on what's worth doing: Define the problem and the trade offs before anyone builds.

- Deliver targeted initiatives: Integrate solutions that tie directly to outcomes, not experiments.

- Sustain momentum with capability: Leadership, governance, and operating discipline that make gains stick.

The best place to start is a simple AI Opportunity Audit.